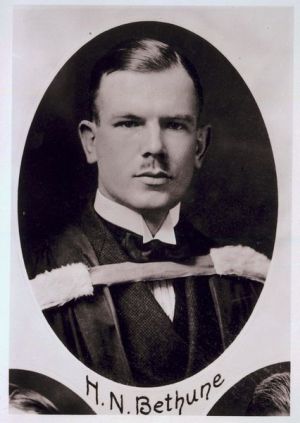

Part I: Pre-China Endeavors and Accomplishments

Dr. Norman Bethune went to China in 1938 to offer support to a peasant army combatting Japanese aggression then died less than two years later. This year marks the 75th anniversary of his death in China. To this day Bethune, Báiqiú’ēn (白求恩), is still viewed a hero in China. Sadly, however, he remains mostly unknown in Canada, a state of affairs I’d like to change.

Dr. Norman Bethune went to China in 1938 to offer support to a peasant army combatting Japanese aggression then died less than two years later. This year marks the 75th anniversary of his death in China. To this day Bethune, Báiqiú’ēn (白求恩), is still viewed a hero in China. Sadly, however, he remains mostly unknown in Canada, a state of affairs I’d like to change.

In my last blog post, I introduced Dr. Bethune. I shared how the courageous example he provided helped me to heal from a serious accident in China. I also wrote about fate and destiny. In this blog I wish to: 1. share more of my personal connection, 2. explore how the concepts of fate and destiny apply to him, 3. provide information about his Pre-China Endeavors and Accomplishments, which led him to the final chapter of his life.

In a later post (Part II), I’ll write about Dr. Bethune’s accomplishments in China and his legacy which still inspires millions today. I might also share recent “fateful” events in my own life which will soon see me retracing the footsteps of Dr. Bethune in China and fulfilling the destiny I’ve been co-creating since my near death in China 9 1/2 years ago.

My Personal Connection with Norman Bethune

My personal connection with Dr. Bethune started in December 2004 while I was working in China. With Christmas coming and being thousands of miles from my family, I was overwhelmed with loneliness. Exhausted too, I needed a holiday. I was preparing a lesson for my Harbin Institute of Technology masters students. (HIT is the equivalent of the USA’s MIT.) “Heroes” was to be the topic. I wanted to tell them about Terry Fox and hear what they knew about Dr. Bethune. Not knowing a lot about Bethune myself at the time, I went online to research. One line that I came across—simple and unforgettable—brought me to tears. The experience was one of identification in which I met the spirit of Dr. Bethune, which is still very much alive in China.

Bethune, far from home and working extremely hard in a vast rugged area of China, wrote to friends in Canada, “It is true I am tired, but I don’t think I have been so happy for a long time…I am needed” (August 21, 1938). Like me, Dr. Bethune felt appreciated and validated in China in a personally unprecedented way.

Dr. Bethune and I had a few other things in common besides Canadian citizenship and personal validation. China changed Bethune, and China changed me too; both of us were teachers who felt called to China (Bethune trained Chinese to be doctors and nurses and I taught English); and for both of us, our time in China was cut short. For Bethune it was a fatal blood infection; for me it was a near fatal car accident.

I entitled my last blog posting Near Death in China, Fate or Destiny? The reference was to myself. If I dropped the “near,” the question could refer to Dr. Norman Bethune. Was his death in China fate or was it destiny? Was it a combination, with his using fate to create a destiny? I am inclined to believe the latter. What is fate, anyway? What is destiny? I’ll start with an analogy here followed by a bigger introduction to Dr. Bethune.

Fate and destiny have intrigued me for a long time, especially after I miraculously survived a serious accident in China. I’d like to compare the concepts to two physical laws operative in our world. Fate I will compare to gravity and destiny I’ll compare to aerodynamics (flight).

1. Fate and gravity:

I define fate as a neutral and impersonal phenomenon, seemingly foreordained, that involves events or things that we have no conscious control over. These events/things often feel as though they happen “to us.” Humans (at least in the Western world) generally associate fate with unfavorable outcomes. In my view, fate resembles the law of gravity and there are roughly two categories, the “natural” and the “human-made.” The natural includes hurricanes, floods and earthquakes.

“Human-made fate” involves the consequences of unconscious programming that’s often activated by our undeveloped egos. Look at the problems galore we humans unconsciously create for ourselves. Consider self-sabotaging behaviour (Norman Bethune was no stranger to this), accidents and illnesses. This kind of fate can often be detected by cyclic behaviour and/or outcomes that do not serve the higher good of ourselves or the people around us. For instance: being drawn into similar kinds of abusive relationships, over-spending, chronic debt, being accident prone, etc. There is a quality of inevitability. Consequences seem to be a “given.” There is no arguing with fate.

In order to loosen the grip of human-made fate, we need to engage in serious self-reflection. This kind of fate must be recognized, examined, learned from and healed. Healing is necessary in order to become conscious, emotionally mature individuals.

In order to create a destiny, fate must be used. There’s no other way.

Like fate, gravity “just happens” and it too with a quality of inevitability. It’s a given. Drop something, it will fall. With its heavy, “unconscious” quality, there’s no arguing with gravity. Its force must be recognized and worked with.

2. Destiny and Flight

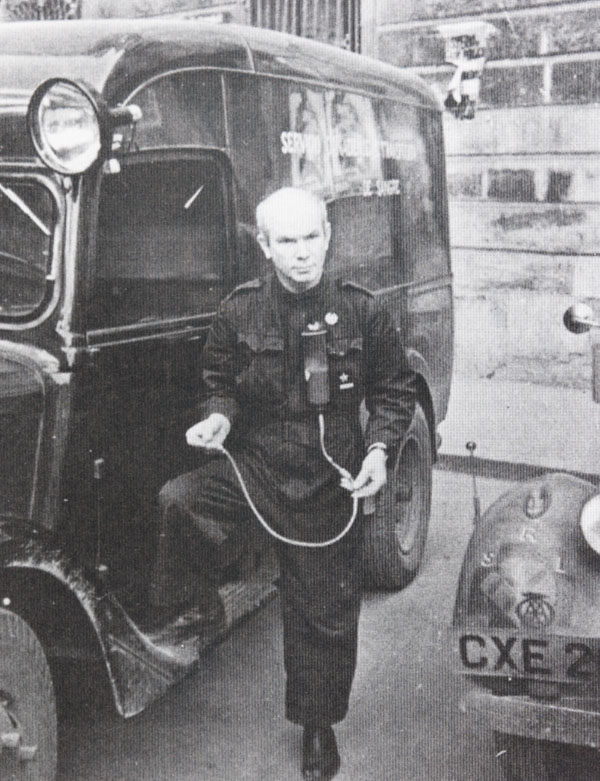

Spanish Civil War, Bethune giving a blood transfusion. Beside him is Henning Sorenson who remarked, “When I look upon the life of Norman Bethune, it seems to me to be one long preparation for the final period–his life and work in China.”

Destiny is something big, unique and special, something that we choose to create. It is our personal big purpose that if fulfilled will leave the world a better place because we lived in it. I believe also that destiny is co-created with a higher power, whether we want to acknowledge that higher power or not. In my view, things work better when we do. (For an elaboration on co-created destiny, please see my last blog post. Click here.)

Destiny is not a given. It demands consciousness, boldness and perseverance. It demands the willingness to move out of our comfort zone no matter how frightened and resistant we may be. In order to create and work towards fulfilling our grand purpose, we must first learn from fate, particularly the human-made variety. (I recall Ram Dass’s inimitable statement, “Earth’s the ‘stay-after-school and learn-your-lessons’ planet. Are you going to get with the curriculum?”)

Learning our lessons helps us gain the strength and courage to identify and create our destiny, thereby transforming our garbage into gold. (Not easy and it’s worth the effort.) In this way, destiny’s creation is much like the law of aerodynamics.

Human flight (aerodynamics) requires the understanding of and conscious use of gravity. (Gravity is part of a slower, denser order of being and doesn’t need to know or understand flight to do what it does. The same holds true if we substitute the word fate for gravity and destiny for flight.) Human flight also requires vision, effort and diligence. How else to get an airplane off the ground or a rocket launched? How else, metaphorically speaking, to launch ourselves into the lives our spirits yearn for, that which we were born to be and do, also known as our destiny? (Again, for more in-depth views on fate and destiny, please see my last blog.) Once again, it’s necessary to use fate to create destiny.

Where was Norman Bethune in all this?

His last months, Wutai Mountains, Shanxi, China. The demand for his services endless, Bethune hardly stopped working. Exhaustion had a way of breaking down his defenses, both physical and egoic.

Just like the rest of us humans, Bethune was mired in “unconscious stuff.” From my extensive reading, however, I have noticed something key about Bethune during his periods of defeat. The more conscious awareness he was able to bring to his personal failings, the more able he was to use disillusionment as a catalyst to pick himself up and proceed with clearer vision. For instance, after insisting on a radical procedure to treat his tuberculosis, which saved his life, Bethune went on to become a thoracic surgeon.

In January 1938, in response to personal defeat in Spain, Bethune chose to go to China, a nation fighting for its survival against fascist aggression from Japan.

From early in his career as a physician, up to the time of his death in China in November 1939 (less than two years after arriving), “fate” had a special way of dealing with this man’s stubborn, and at the same time fragile, ego. The horrors of World War I as a stretcher bearer, his own personal struggles with tuberculosis, and his tireless efforts in doing blood transfusions at the front during the Spanish Civil War (Spain was a “scar on his heart”) had all had their effect at chipping away his ego. It was in China, though, that his unconscious ego was cracked open as he literally worked himself to death and into the ranks of legend.

Norman Bethune—Destiny in His Bones

March 4, 1890, Gravenhurst, Ontario – November 12, 1939, Hebei Province, China

Norman Bethune at 21 working in a lumber camp. He’s in the one in the centre with the swaggering pose.

From childhood, Norman Bethune believed in his bones he was destined to change the world. He was born in Victorian times to religiously zealous parents, a missionary mother and a Presbyterian preacher father, extremely formative figures in his turbulent and troubled life. Indeed, Bethune spent his entire life rebelling against them and, by extension, against everything else he deemed as inflexible, sanctimonious and/or oppressive. In his contrariness, Bethune proved just like his parents in many ways. Like them, he had to be “right”; he had to dominate, and he had to preach (though he chose not Christianity).

With blatant personal problems, most likely beyond his ability to control, Bethune sabotaged himself. Was this his fate, unconsciously self-generated? I think so. Historian and biographer Roderick Stewart in his book Phoenix, the Life of Norman Bethune suggests that Bethune may have suffered from a mental health illness not understood in his day. (Bi-polar disorder?) In any case, in North America and Europe, Bethune’s controversial and often offensive behavior, including his compulsive need to jolt the status quo, led to his unpopularity in professional circles and to lack of acknowledgement for his many achievements, in both the West and especially in China. His communist involvement, towards the end of his life, likely did not help matters either.

Norman Bethune, Pre-China Endeavors and Accomplishments

Many books have been written about Norman Bethune. (I have read several of them.) I have selected only a few (eight) highlights of his life to share here. Each reveals one more stage of Bethune’s “long preparation” leading to “the final period–his life and work in China” (Henning Sorenson, see above Spanish Civil War photo). For those wanting more, I recommend Roderick and Sharon Stewart’s exceptional non-biased, thoroughly engaging biography, Phoenix, the Life of Norman Bethune. I also found great value in the writings of Dr. Bethune himself in a book edited and introduced by Larry Hannant, The Politics of Passion: Norman Bethune’s Writing and Art. (I reached out to Roderick and Sharon Stewart and Larry Hannant in my research on Bethune. I very much appreciate their generous support.) Adrienne Clarkson’s lively and enthusiastic biography, Extraordinary Canadians: Norman Bethune, makes for a good introduction and a much quicker read. Ms. Clarkson has a slight “bias,” which I enjoyed. And, it is understandable, given her Chinese ancestry.

A scene from WW I. Bethune “served” in three war zones in the capacity of saver of life: WW I (stretcher-bearer), Spanish Civil War (mobile blood transfusions), China’s “War of Resistance” against Japan (surgeon)

1. During World War I, Bethune served as a stretcher-bearer in the hell-hole known as “No Man’s Land,” the death zone between German and Allied trenches. Exposing himself to great risk, Bethune ended up having to be carried out himself when shrapnel ripped through his left leg.

Here in Belgium, Bethune realized first-hand the critical need to move medical units closer to the front in order to save innumerable lives otherwise lost. The experience affected his choice of involvement in the Spanish Civil War and later in China, where Bethune was the first to institute the practice of retrieving wounded soldiers from an active battlefield.

2. Early in his career and at the urging of his social conscience (undoubtedly acquired from his parents), Dr. Bethune ‘s mission was to eradicate preventable illness. His remarkable survival from tuberculosis (the “White Plague”), the most prevalent disease of his day, fed this passion and prompted him to retrain as a thoracic surgeon.

During this period of his career, he was able to put his creative and pre-eminently practical skills to work. He both invented and improved upon instruments designed for thoracic (chest) surgery. Later in China, he used this same kind of innovative ingenuity to modify available materials to serve other pressing needs.

3. As a practicing physician in both the USA and Canada during the Depression, Bethune decried the lack of support for those who suffered the most. He saw how the social conditions of poverty made tuberculosis epidemic.

Bethune unsuccessfully appealed to and then rebelled against the Establishment in his passionate advocacy for universal health care. This was 30 years before medicare became a fact in Canada. By challenging (bucking) the status quo, it’s easy to see how Dr. Bethune made enemies galore in both medical and political circles.

Bethune unsuccessfully appealed to and then rebelled against the Establishment in his passionate advocacy for universal health care. This was 30 years before medicare became a fact in Canada. By challenging (bucking) the status quo, it’s easy to see how Dr. Bethune made enemies galore in both medical and political circles.

4. Bethune opened a free medical clinic in Montreal for the poor. (He also started a free Children’s Creative Art Centre for disadvantaged children.)

5. In the mid-late 1930’s, Bethune denounced Western political complacency in the face of fascist aggression in Spain, Hitler and Mussolini’s practice ground before World War II was actually declared three years later. Thoroughly disillusioned with Western tacit support for fascism (what he saw as the turning of a blind eye to it), Bethune made the pragmatic decision to join the communist party, the only organization he felt was serious in combating fascism.

Bethune purchased an old ambulance in England and brought it to Spain where he converted it into a Canadian mobile blood transfusion unit.

6. Zealous to save the world from fascism and its being a cause big enough to utilize his prodigious talent and power-house energy, Bethune went to Spain in 1937. He’d survived the “White Plague” of TB; now he was taking on what he called the “Black Death of modern times,” fascism. In Spain he advanced the already existing, though virtually dysfunctional, mobile blood transfusion service by creating and leading a Canadian unit, which took blood right to the front lines of battle. With an audacious spirit, he saved many lives and developed his expertise in battlefield medicine. He also indulged in self-sabotaging ways, which alienated him from the very people whose respect and support he valued most. He was told to leave Spain.

7. A medical warrior and impassioned propagandist against fascism (he held no punches), Bethune returned to Canada and went on a trans-continental speaking tour to raise funds for Spain. He proved a passionate, powerful orator who drew crowds of thousands to hear him speak.

8. Eager to make a difference and disillusioned with the medical establishment in Canada and the USA (where he’d already burned his bridges anyway), Bethune turned his sights on a war unfolding in Asia. On January 8, 1938, under the auspices of the China Aid Council, Bethune set sail across the Pacific to devote all his heart, soul and physical strength to saving China from the enemy he hated most of all, fascism.

In a new but ancient land, Bethune still struggled against his demons. There was, however, no unnecessary need to struggle on the outside. The uncomplaining example set by the quietly brave soldiers and civilians he worked with helped Bethune re-align with his highest ideals. He gave the best he had to give to China.

Here is a video that provides a good overview of Bethune’s life, with commentary and photographs. There are some inaccuracies and it is biased. It is still worth seeing. The enthusiasm of the young man who created the video is refreshing.

Overview of Bethune’s Life

For an account of Bethune’s “fateful” and heroic final chapter in China, please stay tuned to my next blog, “Dr. Norman Bethune, China’s Canadian Hero, Fate or Destiny? Part II.”

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this well-written and well researched article on the life of Dr. Bethune. I appreciate how you explore fate and destiny as themes that provide a level of depth and opinion to your subject that is often missed in biographical writing. Thank you!

CK, thank you. If I’d actually known Bethune, the man, I may or may not have liked him. There is, however, something about his enduring spirit that continues to fascinate me. I’ve not shared online all of my China experience involving him. (I do so in my book Dancing in the Heart of the Dragon.) Norman Bethune lived life on his own terms and he lived life big. The do-able ideals he stood for and the legacy he left the world move and inspire me to be the biggest, most noble person I can be. This fall in China, my “retracing his footsteps” will undoubtedly open my heart even more. Thank you for taking the time to respond.

I learned a lot about Norman Bethune from reading your post. I like the picture of him relaxing in nature in China. I’m glad he found a place he felt happy with before he lost his life. Sounds like he helped a lot of people in a huge way when they were very injured.

Yes, Bethune was happy at the end. In a worldly way he had virtually nothing, yet towards the end of his life he felt like a king. He was surrounded by people who respected and cared about him, and he felt the same way towards them. The ugliness of guerrilla warfare contrasted with the remote, rugged beauty of the area they were in. He wrote about that beauty and felt blessed. Thank you for taking the time to share your feelings.

I thoroughly enjoyed this post and learning about Bethune! What a real researched and thoroughly engaging article. Brilliant to use the theme of fate as the catalyst for this story. Looking forward to the next chapter:)

Thank you, Jacqueline. I’m glad you found yourself engaged. That man’s life and death have certainly engaged my mind and imagination; even more so, I suspect, when I return to China this fall to “retrace his footsteps”!

Ramona, I loved this post and I learned things not previously known. I did know that Dr. Bethune was and remains a hero in China – what I didn’t know was that he was there for only two years. For all he was able to accomplish, that is unbelievable. Thank you for your research and I do hope that this post will reach many Canadians. We are often so ‘humble’ that we forget to laud our heroes. Thanks.

Lenie

Hi Lenie,

Bethune was actually in China less than two years; 22 months and a couple of days, in fact. True heroes have the capacity to uplift us all. I believe it’s time for more people to be introduced to Dr. Norman Bethune and his remarkable humanitarian accomplishments. Any suggestions to help me in achieving this would be most appreciated! Thank you for your responsiveness.

Ramona

Well written and well researched article. Thanks for writing about Dr.Bethune. I didn’t know him.

Thank you so much!

Like so many great people of history it is the unlimited amount of energy and passion required to carry forth the expectations he held for himself. A very engaging article Ramona on a man I had never heard of before today. The reference you make to bi-polar is certainly one that has been used to explain the behavior of many but one thing appears to be for sure. He had tunnel vision and when his passion claimed a cause to be worth pursuing, he pursued it to the end. I look forward to part two.

Hi Tim,

You wrote: “when his passion claimed a cause to be worth pursuing, he pursued it to the end.” Indeed. Bethune was a man of passionate conviction and he’d let nothing stand in his way. His manic energy drove him to achieve the unrealistic, but it was of course impossible for him to sustain that kind of frenzy for long. If he’d been able to contain himself and to say (many times) “enough,” he could have achieved more “success” in the short term. But then that was not who he was. By sacrificing his life, I think he may have made a far greater difference than if he’d not. It was fortuitous that Mao wrote a eulogy, which essentially immortalized Bethune. His inspiration for good will continue for a long time.

I am returning to China in about a month to join a group of humanitarian Canadian doctors inspired by Bethune. (Only a few of those Canadian physicians are Chinese.) I am glad you are looking forward to reading part II, and I am grateful that you find my writing engaging. Thank you for your comment.

Ramona

Ramona, thank you for sharing your beautifully researched and written article about Dr. Bethune. I love your use of Fate and Destiny. So appropriate. Having been raised in a very devout Christian family (father a minister) I too rebelled and yet have an appreciation for their many good traits and service to help people. I thoroughly enjoyed your article.

Thank you, Beth. I feel honoured that you enjoyed my blog.

Wow! I’m trying to figure out how this is someone who I have never heard of. What a fascinating story and what a connection you share with him. Not to mention the whole aspect of fate and destiny. I could relate to your association of fate/gravity and destiny/flight….such an interesting topic isn’t it? I look forward to learning more of your experiences as well as those of Dr. Bethune’s.

Hi Pamela,

I feel moved and inspired to share my understanding of Dr. Norman Bethune. In the West, as I’ve already mentioned, he’s a virtual unknown, even in Canada. His memory deserves far better than that. The spirit of the man is certainly playing its role in my own unfolding destiny. I am returning to China this fall with a group of humanitarian Canadian doctors. Neither they nor I would be going to China on this trip were it not for Bethune who died almost 75 years ago.

I work very hard with my writing to get my meaning across as clearly as I can. That you could relate to fate/gravity and destiny/flight is helpful. Thank you for letting me know, and thank you for your encouragement.

Blessings to you,

Ramona

Hi Ramona; This was your best written post so far. You obviously have a passion for the subject as well as a wealth of knowledge on the man. It is sad that he lived such a short time. I tend to think that many of us are bipolar. i don’t mean in the clinical definition. but even healthy people have those times of doubt and even depression followed by other times of confidence and triumph. thanks for sharing this special person with us, max

Hi Max,

Thank you for such a complimentary response. 🙂 I don’t know if Bethune was bi-polar or not. He certainly was manic: a power house of energy and relentless drive that thoroughly burned him out, rendering him too depleted to fight a serious infection.

Yes, it is true. I do have a passion for sharing what really is my wealth of knowledge on Dr. Norman Bethune. I believe the spirit of the man is not yet done with helping our world to heal. People just need to know who Bethune was, what he did, and what he stood for: a world where people could be free to live healthy, creative and fulfilling lives.

Thanks for your comment, Max, and I look forward to sharing more of Dr. Bethune with you soon.

Ramona

There are people who move through history unnoticed. Some do nothing to be noticed, others should be but aren’t. I am glad you were able to document this man’s contribution to the world.

There are a number of books on Bethune. May I and the writers of those books help to bring much more public awareness to the life, accomplishments and overall inspiration of Dr. Norman Bethune. Thank you, William, for your comment.

I very much enjoyed this post. I was totally unaware of Bethune and what he did. I found your article informative and engaging. Fate as a catalyst, plays a part in many stories like this. So I applaud you for using it in the way you did. I very much look forward to the next installment. 🙂

Hi Susan,

I can’t know how my writing “lands” for others unless readers tell me. Your encouraging feedback is much appreciated! I’ll look forward to your feedback on part II which is about Bethune in China. 🙂

Ramona

I really enjoyed reading about the life of Dr. Bethune. it must have comforted you to realise that you were following the footsteps of a fellow Canadian and have survived to tell the tale.

I’m glad you enjoyed reading this blog, Mina. I don’t know if “comforted” is the right word. Perhaps “surprised” is. I marvel to consider how a personal traumatic event has shaped what I am doing today. Thanks for writing.

Great post Ramona and you did serious research on Dr Bethune. I especially liked your break down on fate and destiny. I have heard people say “it is my destiny” on things they can actually do something about, I see now its more laziness to change outcomes. Very enlightening and educational post.

Thank you, Welli. Yes, I did some “serious” research, and a lot of serious reflection! I’m glad you found my writing enlightening and educational, and not too serious, I hope. 😉 Thanks for commenting.

I read your post word for word , literally ,afraid of missing anything,and of course my english is not so good .I had to say that :you did a great job ,Ramona! Your analysis is reasonable and vividly.

What impressed me most is that the comments and the replies, the interaction.I could understand the post in many ways.

I think it`s hard to change the character for everyone.You try to cultivate yourself , but it`s still hard to be another guy.So there`s an old Chinese saying:at the age of three you can see his character at eighty.To be a hero or great person surely depends on your endeavor,but the key point is the right time and the right position.That`s what we call fate.That`s what made Dr Bethune seem different in China and abroad.When your time and your mission comes, you try hard to accomplish it , that`s how you control your destiny.

Hi Tommy,

One of the most wonderful things about travelling is making new friends. It’s so great to hear from you, and thank you for reading my blog!

I too am impressed with the comments people leave and I cherish the interaction. Your perspectives on fate and destiny intrigue me and I must say I’m inclined to agree. Bethune’s going to China was fateful; 1938-1939 was “the right time” and China was “the right place.” He was filled with an urgent sense of mission to help the Chinese, and he indeed “tried hard to accomplish” his mission. He gave everything he had in the process, including his life. I believe Bethune fulfilled his mission and his destiny. Do you agree?

You wrote: “there`s an old Chinese saying: at the age of three you can see his character at eighty.” How interesting. Can you help me understand this saying? Does it mean that implicit in the young child is his adult self? That basic character is set early in life or maybe we are born with it? I believe we are born with a certain temperament and particular propensities/leanings. What happens in our lives, the way our parents guide us or not guide us and the choices we make all play their part in the development of our character. This topic would certainly make an interesting topic for discussion.

I have not as yet written about my recent trip to China. I’m in the midst of organizing my photos, which will play a big part in the next blog I write. I’d be happy for your comments on that one when the time comes.

It’s wonderful to be in touch, Tommy. Best wishes to you and your family.

🙂 Ramona

This morning I picked up my very old NFB copy of “Bethune” (VHS), and went to the computer to search ‘NFB Bethune’. I was looking to find out how I could get a clean digitized copy of the film, rather than a scanned VHS version. The NFB site popped up and as I scrolled down, there was a comment from Ramona which caught my eye. I went to the link she offered & here I am, reading all the wonderful comments everyone is making about Dr. Bethune.

I would say that Dr. Bethune was the most important role model that got me involved in living and doing medical work overseas, more than 40 years ago. He is still my main inspiration. As I near the end of my active clinical career, I feel honored to still be honoring Dr. Bethune’s memory, 80 years after his untimely passing. It is good to know that there are still those who cherish his acts of commitment, and the loud, positive criticisms of his time. Great blog and website. Thank you.

Mickey, thank you, for taking the time to comment. I’m so glad you found my link on the NFB site. All the best to you.

Profoundly beautiful Ramona!

My, thank you, Jan!